A strong foundation is essential to any endeavor that’s meant to last, and Texas State University’s first 30 years were an illustrious start to the legacy we continue to build today. An unwavering dedication to our mission guided us through our early years of growth and some turbulent times. Many of the experiences and traditions that define being a Bobcat today have their roots in this first era of our history.

Our Continuing Mission

From our founding 125 years ago, Texas State has been focused on empowering our students through education to create a brighter future for their communities. In the beginning, this mission was singular and straightforward: “prepare worthy teachers for the schools of Texas.”

Between 1880 and 1900, the public education system in Texas expanded by nearly 200%, from 176,245 students to 515,544. The state desperately needed trained teachers.

To fill this gap, the state turned to normal schools — schools that were focused on equipping future teachers “with the fundamental principles of the science of education and the art of teaching.” Normal schools were schools that were focused solely on training future teachers. Normal schools did not offer a college education or award degrees.

The people of San Marcos were fervent supporters of education. Local historians Dudley R. Dobie and Annie Hall have credited the area with 40 schools before TXST was established. And in the 1880s and 1890s, the hill that is now home to Old Main hosted a local Chautauqua that provided education and entertainment in the form of sermons, outdoor recreation, lectures, and discussion of social reforms.

Community leaders lobbied for a normal school in San Marcos, believing it would benefit the entire region by making it easier for people in the area to become teachers and serve their local schools.

On May 10, 1899, Governor Joseph D. Sayers approved a bill establishing Southwest Texas State Normal School in San Marcos.

On October 16, 1899, the San Marcos mayor and city council approved the transfer of Chautauqua Hill to the state for the normal school. The hill would be an ideal place for a school, with green hills, a limitless view, and a pure river at its base. Citizens boasted of the effect the location would have at a meeting in 1901: “The river … will prove suggestive of high aims and noble ambitions, and the green hills will have their influence, giving to the State … teachers who, while drinking deep from the fountain of knowledge, will have absorbed from their surroundings an ennobling influence, a sense of duty that will impel them to their best efforts.”

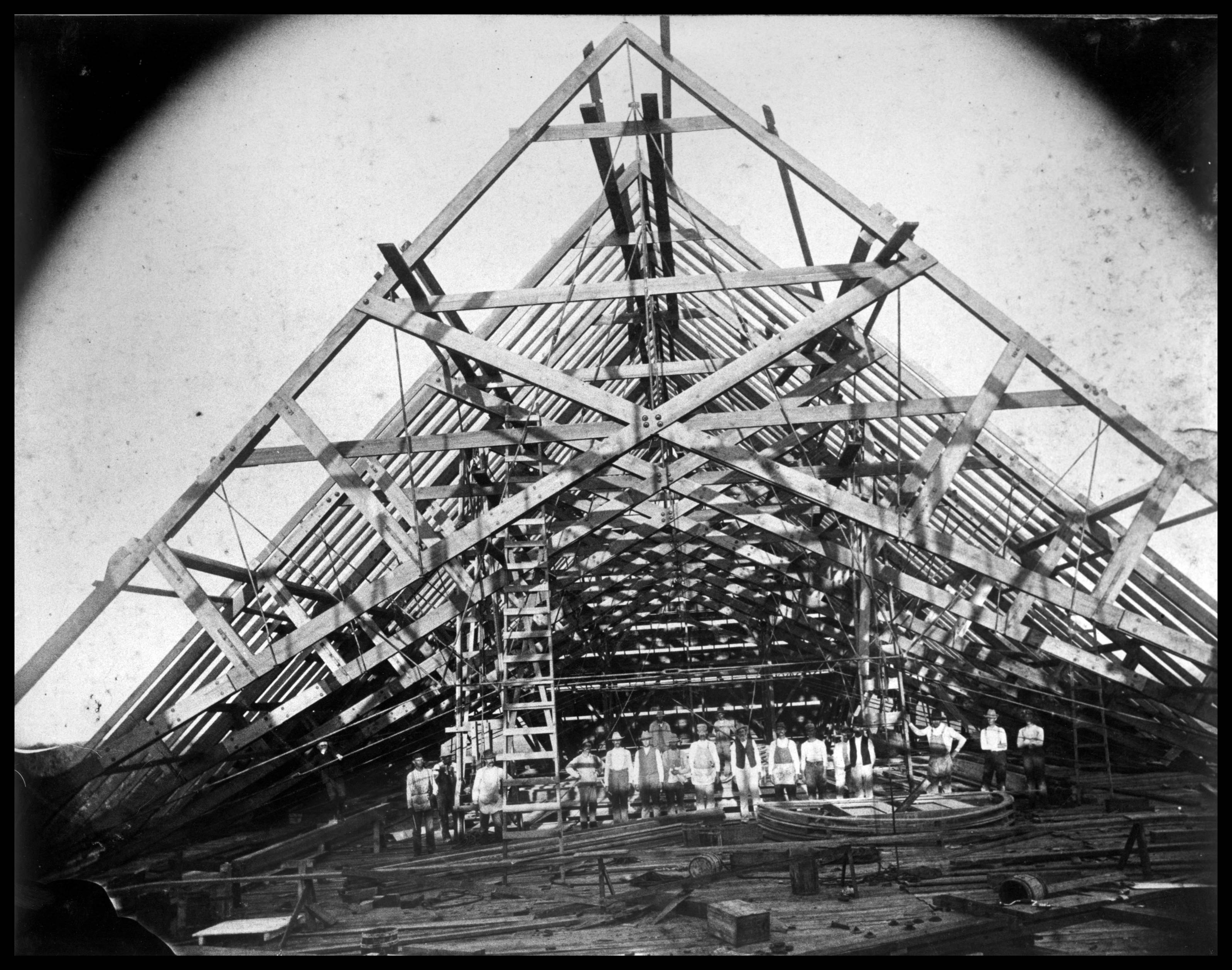

Construction of Old Main began on the hill in 1902, with Gov. Sayers in attendance to help lay the cornerstone. Though construction proved complicated, the building opened in time for classes to begin in September 1903.

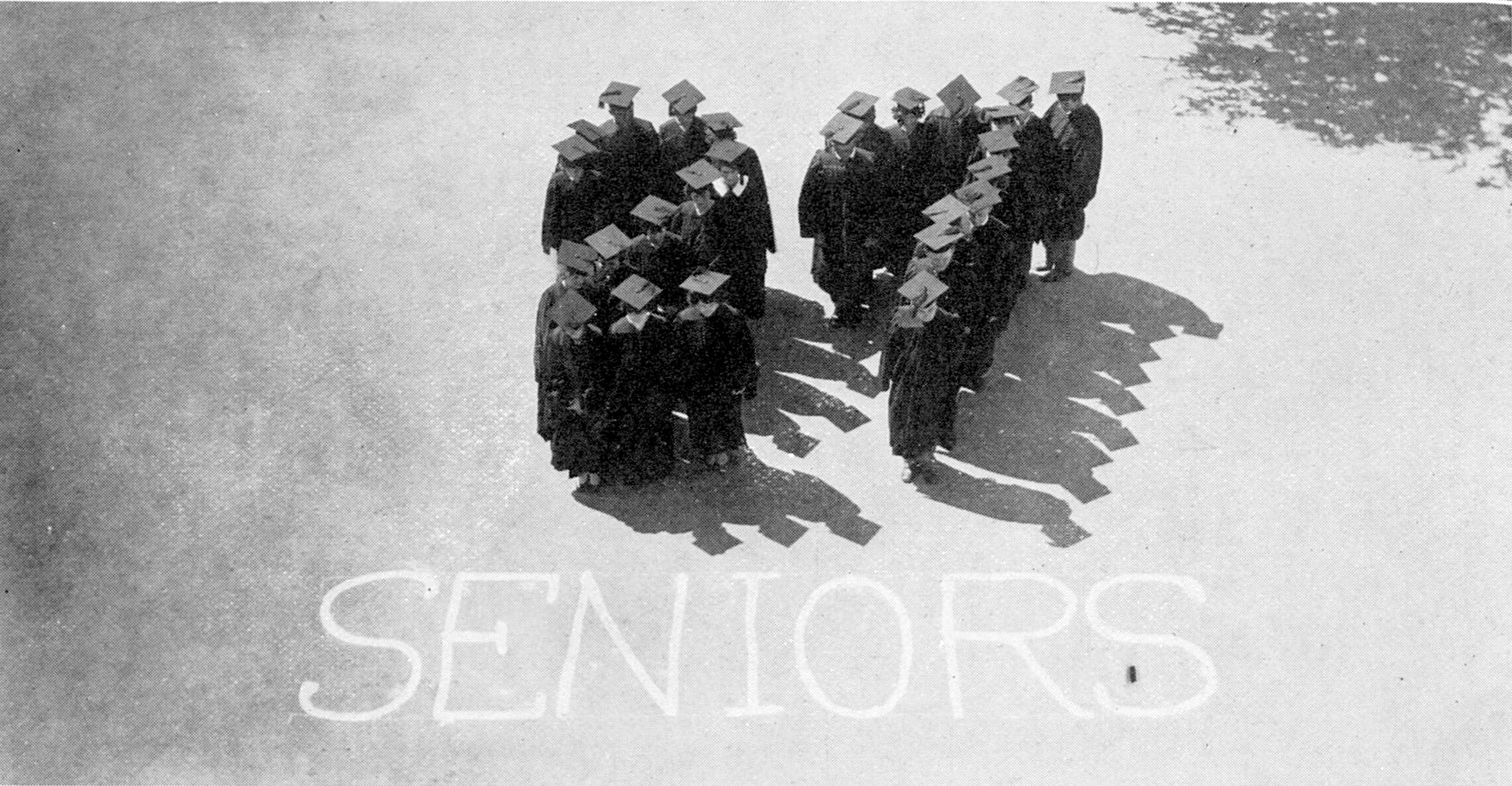

The first 303 students at Texas State were as young as 16. They had to be residents of Texas, or promise to become Texans, and pledged to teach in public schools for at least as many sessions as they attended on the hill. After three years of courses, students earned permanent state teaching certificates.

Texas State’s dedication to its mission would shape much of its early growth as an institution. Each change to TXST in its early years was driven not just by the state’s continuing need for teachers but also the recognition that “the schools of Texas are demanding teachers of thorough academic training and a high degree of professional skill.”

In 1913, the school was elevated to a junior college with the addition of two years of college work, and in 1914, a training school for teachers to practice opened on campus. In 1916, the Board of Regents authorized two more years of college instruction, making TXST a standard college. TXST students could now earn a bachelor of arts or bachelor of science in education.

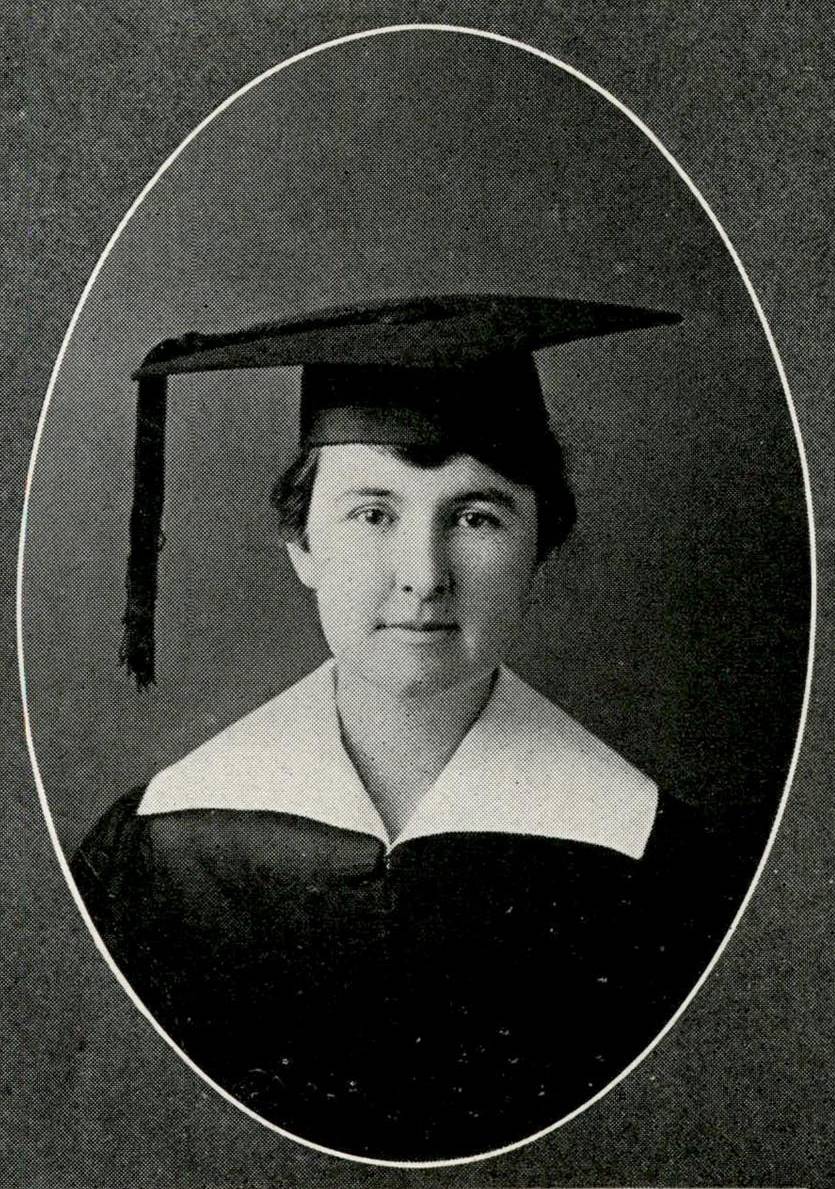

In 1919 — a year before women earned the right to the vote with the ratification of the 19th Amendment — Mamie Brown became the first person to earn a degree from Texas State. Brown had earned a permanent teaching certificate from the school in 1910 and returned later for a fifth year of work and another certificate, before returning once more to earn her degree. She would go on to become a faculty member at Texas A&I (now Texas A&M-Kingsville).

The shift in the scope of Texas State’s work to fulfill its mission was also apparent in the two name changes of the era. In 1918, the school’s name was changed to Southwest Texas State Normal College, and in 1923 the name was changed to Southwest Texas State Teachers College. It was apparent by this time that teachers colleges needed to appeal to talented students.

“To attract such students to the work of teaching … nothing less than a four-year college course meeting the standards of the most exacting colleges answers this purpose for the most ambitious young men and young women.”

– The Southwest Texas State Teachers College 1923-1924 Catalog

Many of the students educated at Texas State during this early era would teach in Texas communities, and the work they did to train “the minds and characters of the children of this generation” was seen as a “constructive force for community development.”

Leading the Way for Others

Education in Texas was segregated in the early 1900s, and Texas State was not an exception to this rule. While Black students wouldn’t gain admission until 1963, the first Hispanic student enrolled in 1906.

Elena Zamora O’Shea was born on July 21, 1880, in Hidalgo County. After attending Texas State, she taught for more than 20 years and went on to become a prosperous businesswoman, translator, and author. Zamora O’Shea’s 1935 historical novella, El Mesquite, “is a literary and historic work of lasting value, which clearly articulates the Tejano claim to legitimacy in Texas history.” The book detailed daily life, Tejano cultural traditions and folklore, local plants and folk medicines, foods and recipes, and more.

In the late 1920s, more students with Hispanic surnames began to appear regularly in the pages of the Pedagog, the school’s yearbook.

In 2021, 115 years after she enrolled at Texas State, a residence hall was renamed Elena Zamora O’Shea Hall to honor her legacy.

The First World War

When the United States declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, it had a profound effect on Texas State. Enrollment plummeted from more than 1,000 students to nearly 300 as many young men enlisted in the armed forces. More than 400 students and graduates served in World War I.

In September 1918, the school received a training unit of 80 men, who were quartered in an empty building on campus, fed, and drilled until the war ended in November 1918.

Six TXST students and graduates lost their lives during the war: Jack Arnold, Kenneth Gardner, Joe Stribbling, Henry Whipple, David Haile, and William Harris. A monument to them stands in the Veterans Memorial Garden today.

History Professor M.L. Arnold, whose son was killed in action in France, penned this poem for the 1918-1919 Pedagog:

The Deathless Dead

The deathless dead, they shall not die,

They’ll still live on in memory and dreams,

Tho’ far away their mould’ring bodies lie,

Where once rang out the golden bells of Reims,

On Argonne wood or Flanders’ harried plain,

By Verdun’s scarred and crumbling piles,

While ’round them once more springs the ’rip’ing grain,

And o’er their tombs the blushing poppy smiles;

For freemen in the coming years,

As long as men are free,

As long as Valor’s death endears,

As long as honor yet may be,

With words of love and looks of pride,

With glowing cheek and kind’ling eye,

Will tell of how they died;

The deathless dead, they shall not die.

Academics in the Early Years

In 1903, all TXST students were training to be future teachers, and they took course work in history, civics, geography, education, vocal music, physical sciences, physiology, botany, mathematics, zoology, English, and Latin or German. Students earned permanent state teaching certificates after three years of work.

Starting in 1916, students could earn a college degree: a bachelor of arts or bachelor of science in education.

By 1929, students could earn a bachelor of arts or bachelor of science with a “professional major” in education and could choose an “academic major” from economics, business administration, sociology, English, public speaking, dramatics, Latin, French, German, Spanish, home economics, mathematics, chemistry, physics, biology, agriculture, history, geography, or government.

Our Athletic Origin Story

Women organized the first sports team at Texas State when they formed a women’s basketball team. In 1923 and 1924, the basketball team won the Women’s Intercollegiate Athletic Association championships.

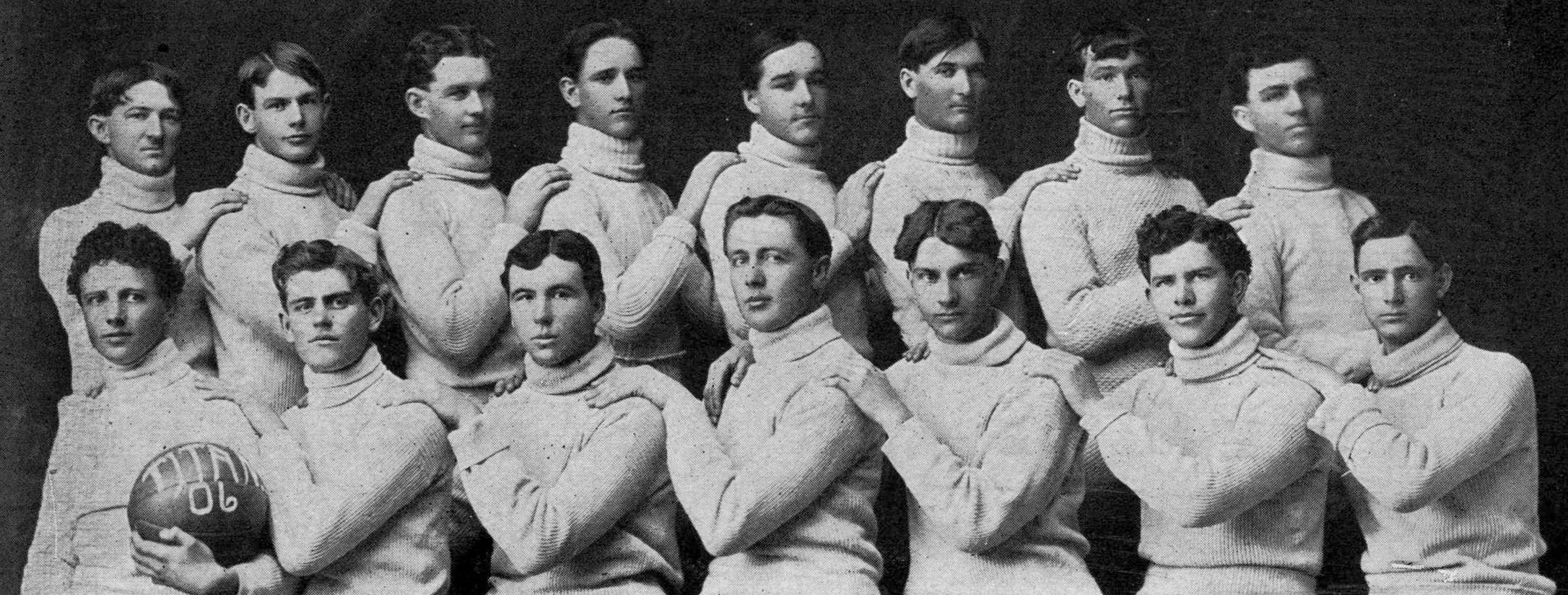

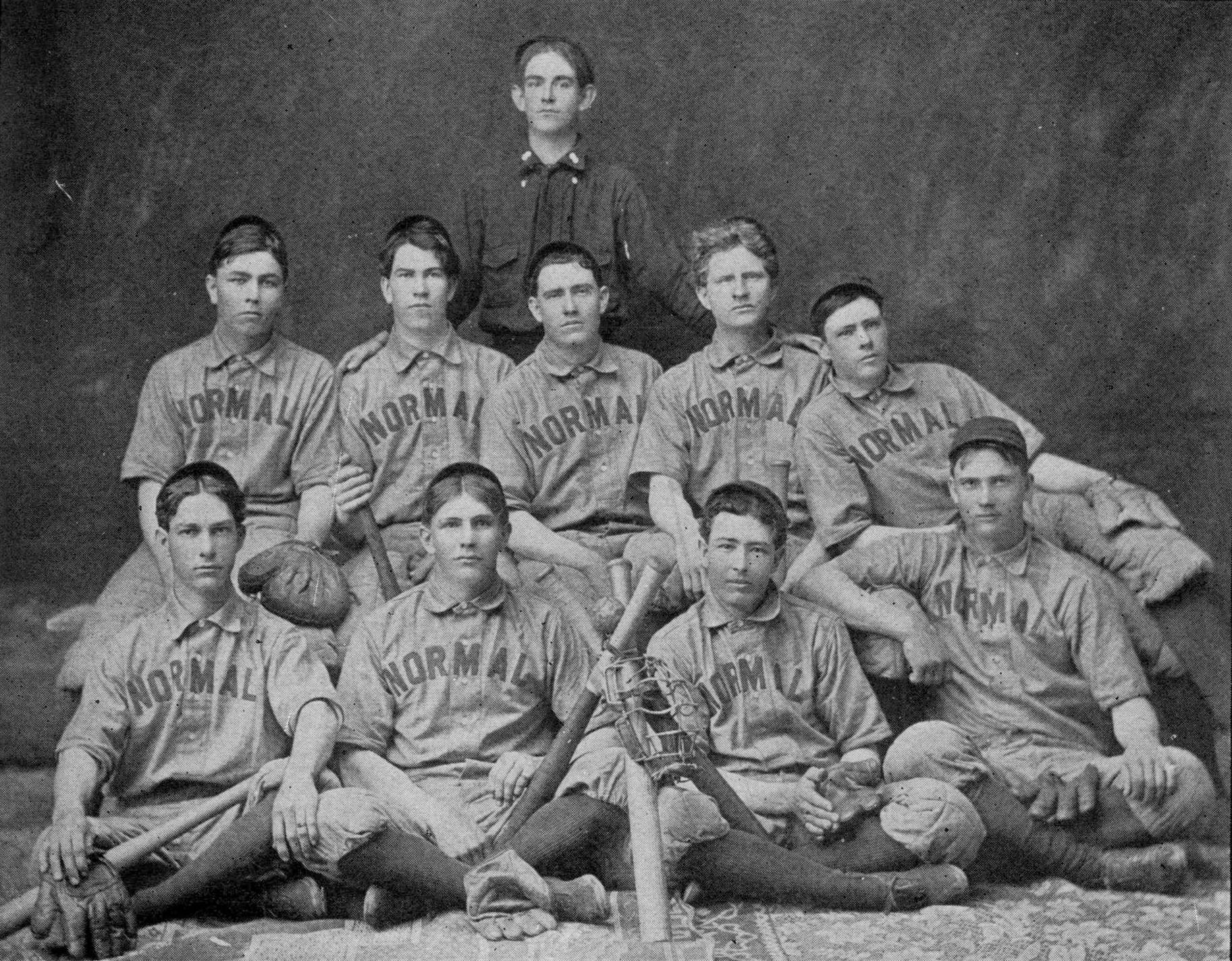

The first men’s teams organized on campus, in the 1904-05 academic year, were baseball and basketball teams.

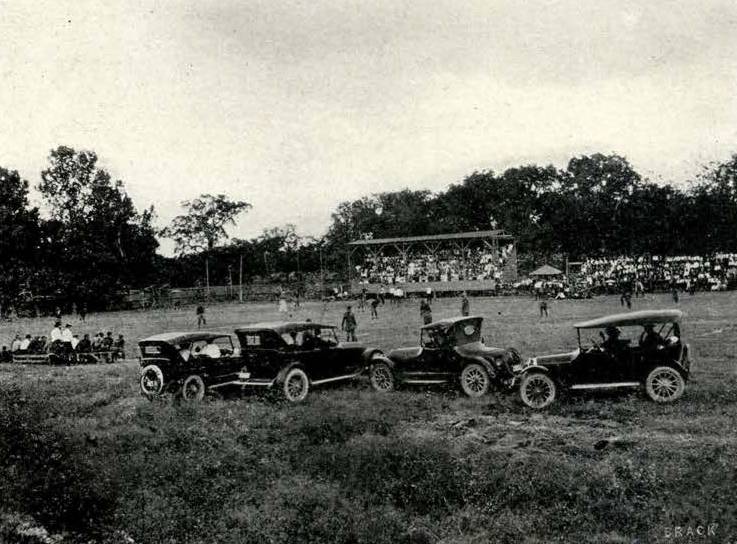

Football came to campus in the fall of 1908 and became a permanent part of TXST athletics by 1910. The football team won conference championships in 1921, 1924, and 1929.

Oscar Strahan, the school's first professional coach and athletic director, joined TXST in the fall of 1919. At the beginning of his TXST career, he coached every men's sport except for baseball. During his tenure as athletic director, he oversaw conference championships for football, men's outdoor track and field, men's tennis, and men's basketball.

Today, Strahan Arena at the University Events Center is home to athletics games, graduation, and other important university events.

Our First Traditions

Many traditions that are beloved by Bobcats today got their start in the first 30 years of Texas State’s history.

The first students to step on campus immediately set about making a place for themselves. The first student organizations they formed at Texas State included the YWCA, literary societies, and three music associations.

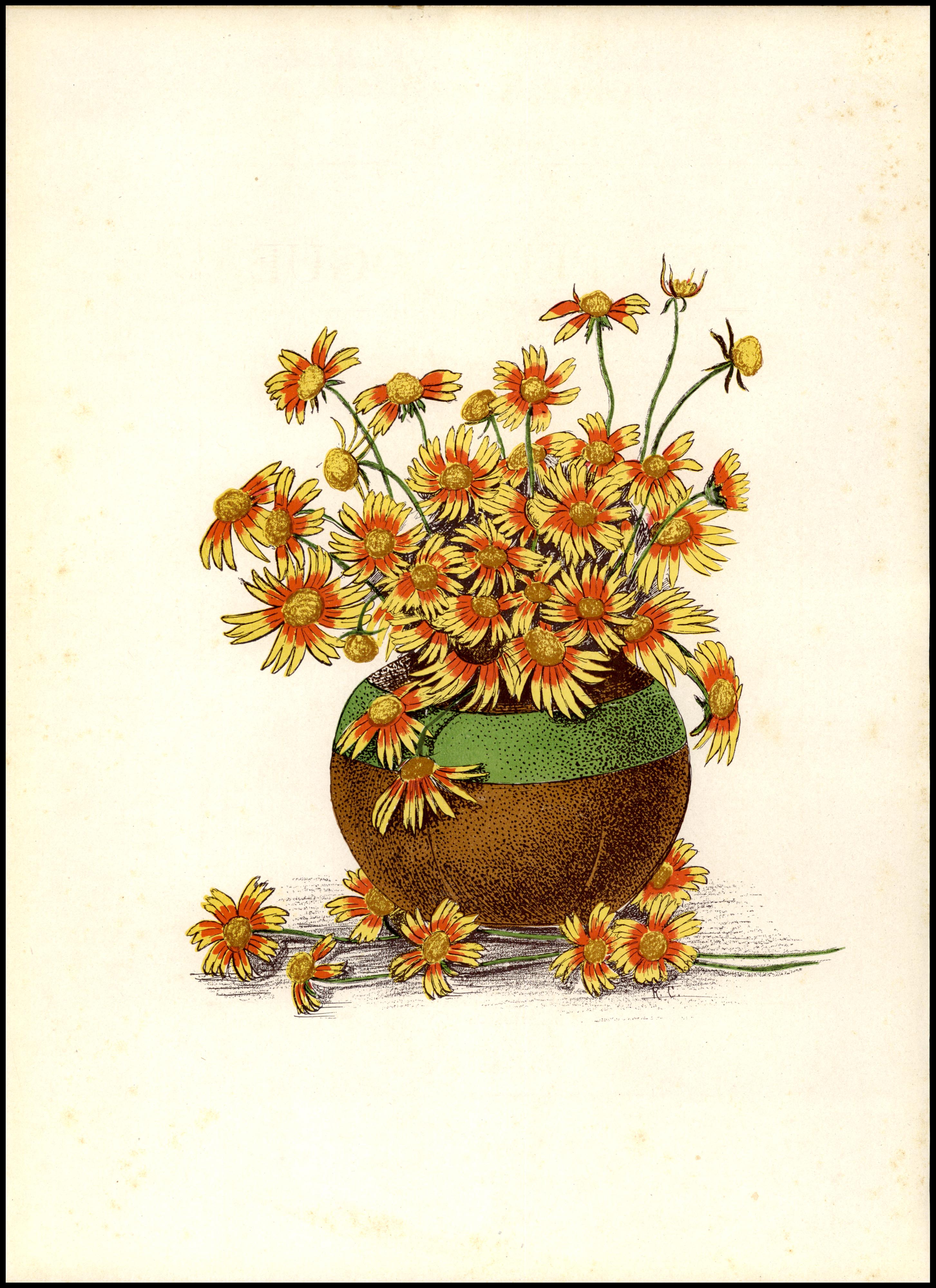

The class of 1905 adopted the gaillardia as their senior class flower, and the gaillardia remains our school flower today. By 1908, the seniors had also declared maroon and gold as their colors, another tradition that remains a vibrant part of our community.

In 1916, inspiration struck when Dr. S.M. Sewell, a mathematics professor, waded into the San Marcos River and decided that the university needed a park. In 1917, the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries leased the college four acres of land along the river, and after some extensive work, the new park opened in the summer. It was called Riverside Park until 1946, when it was renamed in honor of its founder, Sewell.

Our Alma Mater was also created in the early 1900s, appearing in print in a 1916 edition of the Normal Star. The lyrics were written by Jessie Sayers, one of Texas State’s first faculty members.

Homecoming got its start in 1911, driven largely by alumni and students. One of the earliest editions of the Normal Star — the school paper that’s today known as the University Star — urged students to return to campus for a special celebration. The festivities started on May 13 and culminated in graduation ceremonies on May 16. Activities included a commencement sermon, a senior class program, a barbecue, and a baseball game.

In 1921, Homecoming took on a more familiar form when it was moved to the fall to make football the main event. In what the Normal Star called “the most important game ever played on Evans Field,” the Bobcats beat North Texas State Teachers College 14-0, securing the State Normal Championship and capping off an undefeated season.

O, Alma Mater, set upon the green hills,

With turrets pointing upward to the sky,

We yield to thee our love and our devotion;

Mother of hopes and aspirations high.

Thy spirit urges us to deeds of valor,

Raising the fallen, cheering the oppressed;

Thy call will echo clearly down the ages,

Dear Alma Mater, mother loved and blessed.

A vital part of our modern game day experience, the marching band got its start in 1919 with support from the Board of Regents, who donated 11 instruments. D. D. Snow, a student, directed a group of 22 student musicians. The band first performed at a football game on Thanksgiving Day at the original Evans Field, now the band’s practice field.

One of our most recognizable traditions is our Bobcat mascot. In 1921, a committee led by Dr. C. Spurgeon Smith recommended that the school adopt the bobcat as the college’s mascot, and Athletic Director Oscar Strahan approved the selection. Strahan later said: “A bobcat will fight you with everything he has; with four claws, teeth, speed and brains.”

Students Celebrate German Ancestry

German immigrants and their descendants constituted more than 5% of the state’s population in the late 19th century, and many Germans settled in the Hill Country in towns like New Braunfels, Boerne, and Fredericksburg.

This influence was felt at Texas State, where German was one of the first foreign languages offered at the school. Two of the first student music organizations were named after Germanic composers, and the German Club, Germanistische Gesellschaft, was one of the most active clubs on campus until it disappeared in 1919 amid a national wave of anti-German backlash to WWI.

Strict Discipline

The early years of Texas State were marked by strict discipline. Students had to ask permission to leave campus, and they couldn’t receive social calls at their boarding houses after 10 p.m.

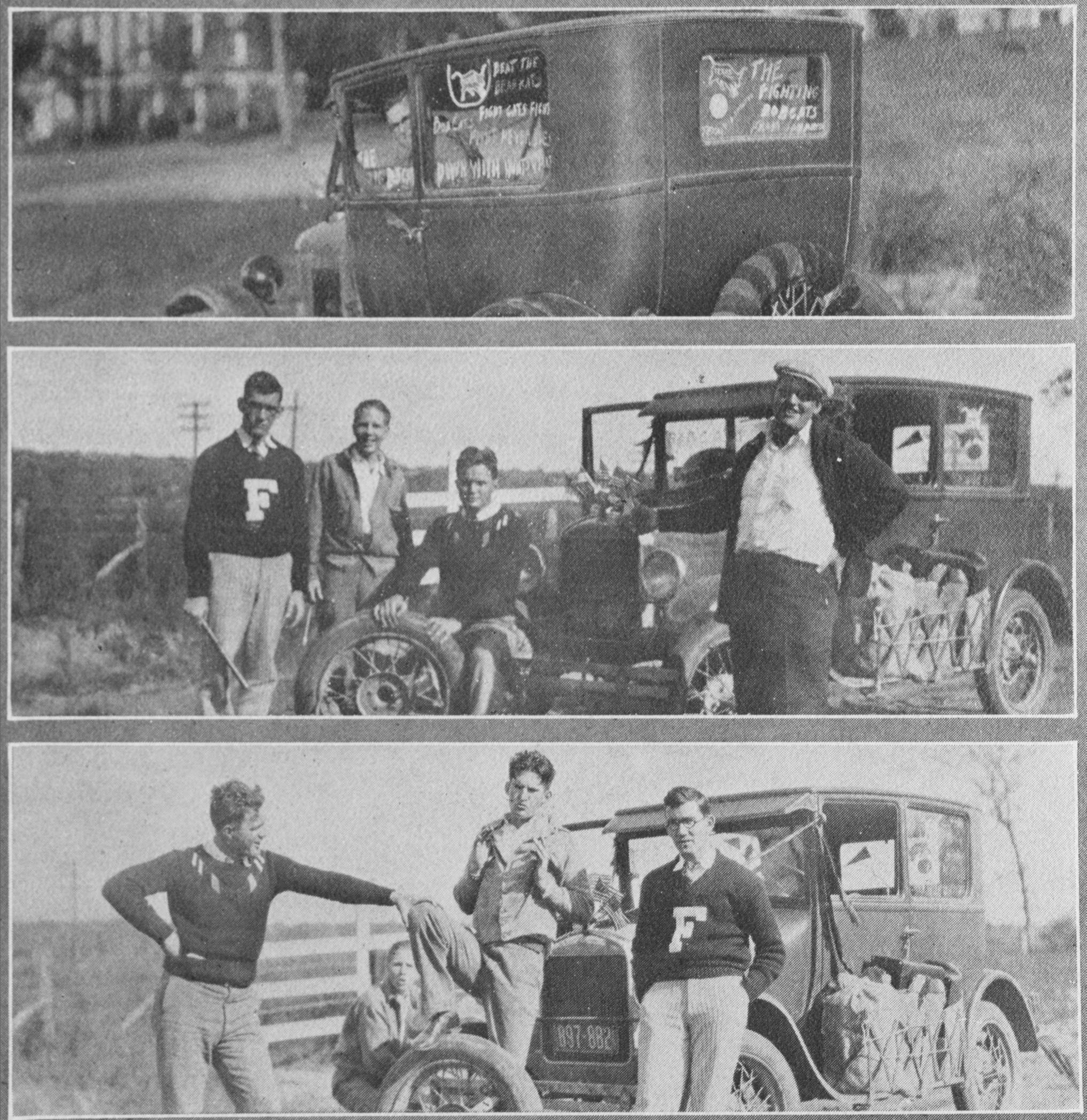

As the automobile became more popular in the 1920s, another regulation forbade "a young woman to enter an automobile with a young man,” reflecting a widespread national concern that boys and girls were spending too much time together “motoring.”